However, they usually ignore the importance of light to regulate our biological rhythms,” explains Martín-Olalla.

According to the researchers, the change to daylight saving time (DST) in spring, which advances the clock by one hour, is not a mere whim of the authorities but is based on the natural delay of sunrise in winter. “The criticism of this practice is based on arguments that ignore the naturalness of the seasonal time change,” says Mira.

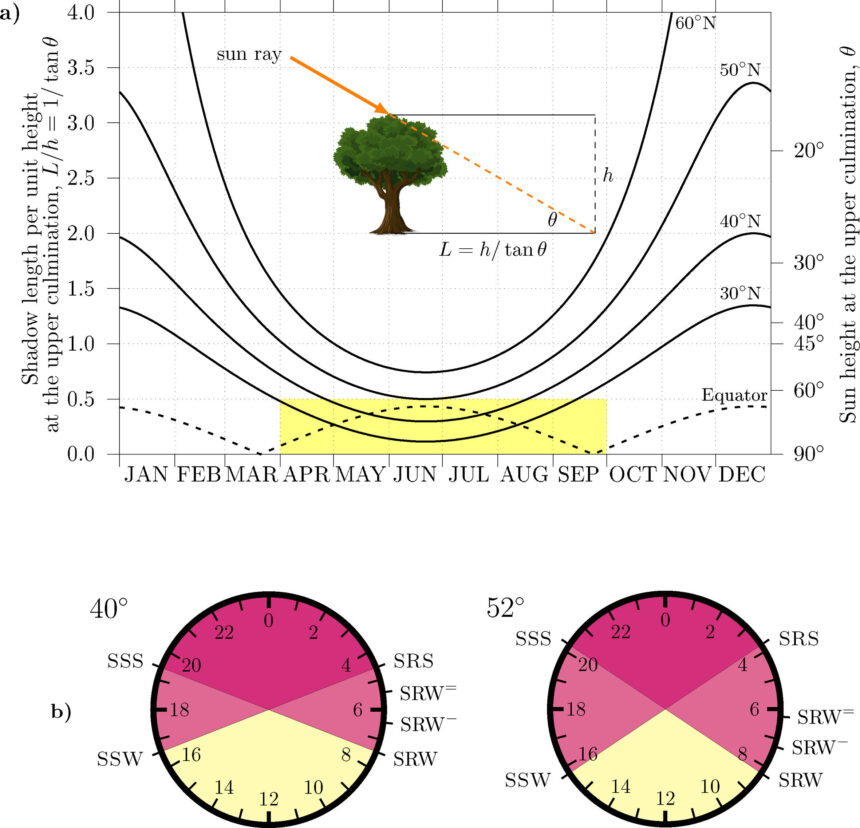

The study also highlights the impact of DST regulations on regions closer to the equator, where the variation in sunlight throughout the year is less pronounced. “In tropical regions, the sun rises and sets at almost the same time every day. This means that the insolation is more tropical and there is less variation in the hours of light and dark,” explains Martín-Olalla.

Overall, the research emphasizes the importance of considering the natural patterns of sunlight in determining the best time to start the day. By aligning our daily schedules with the changing seasons, we can optimize our productivity, health, and well-being.

As society continues to debate the merits of daylight saving time and seasonal time changes, studies like this provide valuable insights into the physiological and social implications of our daily routines. By understanding the natural rhythms of light and darkness, we can make informed decisions about how to structure our days for maximum efficiency and happiness.

The debate surrounding the use of seasonal time change has been ongoing for years, with proponents arguing for its benefits and opponents raising concerns about its impact on human health. A recent study conducted by Martín-Olalla and Mira sheds new light on this issue, providing a comprehensive analysis of the effects of changing the clocks and the controversy surrounding this practice.

According to the study, changing the clocks serves as a synchronizing mechanism that adapts human activity to the corresponding season. The authors suggest that the first weekend in April and the first weekend in October would be the most appropriate times for this change to occur. They argue that this adjustment aligns the start of daily activities with the sunrise, allowing for more efficient use of daylight hours.

When it comes to the impact of seasonal time change on human health, the study distinguishes between the effects associated with the change itself and those associated with the period during which daylight-saving time is in effect. The authors point out that while some studies have reported a slight increase in traffic accidents following the clocks going forward in spring, the overall impact is relatively weak compared to other factors influencing the problem.

Furthermore, Martín-Olalla and Mira criticize studies that attribute long-term health effects, such as increased risk of cancer, sleep loss, and obesity, to seasonal time change. They argue that these studies fail to consider the seasonal nature of the time change and analyze data within the same time zone, which does not provide conclusive evidence of causation.

The authors also challenge the notion that changing the clocks disrupts the population’s natural rhythm and causes misalignment with the sun. They emphasize that this practice has been in place for over a century and has successfully adapted human activity to the changing seasons without serious disruption.

In conclusion, the study highlights the historical success of changing the clocks in the 20th century and examines the challenges faced by medical associations seeking to eliminate this practice and adopt permanent winter time. Martín-Olalla and Mira call for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of seasonal time change and emphasize the importance of considering the natural adaptation mechanisms that have been in place for centuries.