Hemeti’s cheerleaders are attempting to whitewash his history and present his record of atrocities, painting him as a dove of peace to legitimise his war while portraying him and his militia as natural political players with the potential to seize power in Sudan through their collaboration.

Some members of the Sudanese political club who talk about Hemeti say he is being honest or that he ‘never lies’, indicating he is a man of principle.

One of the Civilian Front (Tagadum) members recently assured the public on television that he is a peace hero who has no personal ambitions for power. They are trying to wash away the man’s background and present him in a way that contradicts his history and the reality that all Sudanese currently live and see.

It is a ludicrous attempt that denigrates the grief and suffering of an entire population affected by his atrocities. They are political mercenaries, just like Hemeti’s armed mercenaries. Furthermore, they overlook Hemeti’s deeply ingrained tendency to turn on anyone who allies with him or trusts him to take his side.

Dirty deeds timeline

In 2003, he made his first debut as part of the Bashir regime’s campaign to recruit criminals into the Janjaweed militia for the Darfur war. However, it was not long before he defected and declared an insurgency on Bashir.

By March 2006, he signed an MOU with the Justice and Equality Movement, and in June 2007, he did the same with the Sudan Liberation Movement, headed by Abdul Wahid Nur. Afterwards, he made threats to attack Nyala, one of the biggest metropolitans in Darfur, which his soldiers besieged in October 2007.

Hemeti’s rebellion was put to an end in early 2008 when he was bought back to Bashir’s stable. In return, Bashir bribed him with 1bn Sudanese pounds (equivalent to $440,000 at the time). Bashir also gave half of that sum to his brother Abdul Rahim, with the promise to train and promote 300 of his men to officer ranks in exchange for 3,000 of his men joining the regular army.

Later brought back into the spotlight during the Bashir regime conflicts with original Janjaweed leader Musa Hilal, and his Revolutionary Awakening Council, Hemeti was appointed commander of the newly formed Rapid Support Forces (RSF). They made their first appearance throughout the violent end of the September 2013 uprising.

In their ongoing rivalry over who was more criminal, Hemeti’s internal battles with Bashir regime’s criminals persisted

According to the Human Rights Watch report, the RSF shot demonstrators even though they had stopped. In its initial foray into the city, the RSF killed almost 200 unarmed civilians. After that, in 2014, it declared a new operation in Darfur and the Nuba Mountains called ‘Hot Summer Operations’, adding more brutality to its reputation.

The humanitarian situation worsened beyond anyone’s wildest nightmares since the Darfur war started in 2003. In the first three months of 2014, the number of internally displaced persons surpassed 215,000, according to the United Nations Mission to Darfur.

The number of casualties remains unknown, and dozens of villages were plundered and burned to the ground. By contrast, the RSF’s crime wave in the first quarter of 2014 surpassed all atrocities committed over the preceding decade of the Darfur conflict.

Political and military machinations

In their ongoing rivalry over who was more criminal, Hemeti’s internal battles with Bashir regime’s criminals persisted. The army commanders denounced Hemeti’s militia as an independent group linked to the intelligence and security service at the time.

He also took down the then-minister of the interior, General Ismat Abdel Majeed Abdel Rahman, who had accused Hemeti’s militia of causing anarchy in Darfur in 2015, leading to his removal of his position and subsequent compelled departure from the country.

Hemeti wielded such significant power, to the extent of forcing the Bashir regime to detain former Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi for speaking out against the militia.

Later, Hemeti lost his most significant supporter within the regime, Taha Osman Al-Hussein, the director of Bashir’s office and who played a key role in involving Hemeti and his forces in quelling the September 2013 uprising with extreme brutality.

[Hemeti] exploited his position to circumvent economic measures and to empower and increase the influence of the Rapid Support Forces financial empire.

In 2017, Al-Hussein was dismissed. Shortly after, Abdel Ghaffar Al-Sharif, another ally of Hemeti, was removed the next year.

Al-Sharif was the director of political security in the security service and historically involved in the regime’s crimes against the student movement, most notably the assassination of the martyr Mohammed Abdel Salam, the student activist of the University of Khartoum in 1998.

The two men sought shelter from the previous government in the Emirates’ sphere of influence. The UAE made efforts to secure their release, after which they both relocated there as an official announcement of their full-pledged agency and client to the UAE that also involved Hemeti and his forces.

At the same time, the Islamist Parliament approved the Rapid Support Forces Law in 2017, placing it under the command of the Sudanese army. The situation struck fear in Hemeti, who saw former Bashir regime ally Musa Hilal thrown into prison.

Manipulating the Transitional Sovereignty Council

This led him to join the change movement as the revolution stripped down the regime. With Hemeti on one side and the army leadership on the other, he joined the revolution out of the blue, after its victory was assured and the revolutionaries were besieging the Army General Command buildings.

Hemeti successfully positioned himself as the deputy head of the military council, using his arsenal to advance his ambitions. He disregarded his assurance to move on from the past and played a significant role in instigating, organising, and carrying out the dispersal of the sit-in massacre with the Army leadership in June 2019, under the encouragement of the UAE.

The UAE was concerned about the growing demand for civilian rule in Sudan, which threatened its ambitions to create a client state out of Sudan.

However, the two partners in the crime retreated from their first attempt to take power into their own hands and exclude civilians under global and regional pressure.

By August 2019, a political agreement was inked, which Hemeti signed to launch the transitional period as a compromise solution that broke the deadlock of the post-revolution process.

Hemeti, with the help of his partner at the time and now-rival, General Burhan, imposed himself as deputy chairperson of the Transitional Sovereignty Council without any agreed-upon legal or constitutional reference. It was justified as an internal arrangement in the Sovereignty Council.

However, this internal arrangement resulted in protocol arrangements that Hemeti exploited to the maximum extent in consolidating his power, especially in his dealings with the executive branch.

He exploited his position to circumvent economic measures and to empower and increase the influence of the Rapid Support Forces financial empire. He engaged in gold smuggling, currency trading, seizing state resources and institutions, and even land and home grabbing.

In doing so, he used every possible political trickery to manipulate his alliances with civilians on the one hand and with the army on the other, while at the same time continuing to consolidate his foreign relations as a political actor independent of the state apparatus.

The conflicts within the civilian camp, in which some of its members were not ashamed to enlist the aid of the military – both the army and the militia – to further their political ambitions, helped him in this.

It did not take Hemeti long before reverting to his old customary practice of breaching pledges.

Heading a coup before the world tour

Hemeti actively engaged in the organisation and execution of the coup that transpired on 25 October 2021, ultimately bringing an end to the transitional trajectory. He hurried to diplomatic missions immediately following in an effort to market himself and bolster the coup’s foundations.

He travelled to Russia immediately prior to the onset of its invasion of Ukraine, declaring his support for the Russian actions on the first day of the invasion. In an effort to garner support for their coup, or what they termed ‘corrective measures’, he embarked on a Gulf States tour.

He utilised civilians to rationalise his endeavour to acquire more power and subsequently instigate the war

Shortly afterwards, he engaged in a competition with his accomplices regarding the spoils of their coup-related crime. He initiated a quest for fresh allies and discovered them in civilians who both gave and received assistance from him throughout the turbulent transitional period.

He utilised civilians to rationalise his endeavour to acquire more power and subsequently instigated the war, claiming that he was battling the Islamists, his makers.

Warmonger of ‘racial superiority’

On 15 April 2023, Hemeti initiated his war. His militia’s mercenaries raped women, occupied and looted residences, and damaged civilian infrastructure, all while he and his media platforms talked about civil governance and the return of democratic principles.

He addressed the distribution of humanitarian aid and meeting the needs of the people, all the while the soldiers were pillaging warehouses belonging to the World Food Program and other relief agencies whenever they came across them.

Signing more than 10 agreements in Jeddah to stop hostilities, Hemeti observed none.

He discussed putting an end to discrimination, promoting citizenship and equality, and ensuring the rights of marginalised groups while his forces killed the governor of West Darfur state, Khamis Abkar, and desecrated his body, reinforcing their theories of racial superiority.

They then used their weapons to target and harm the African Masalit community based on race and ethnicity. He expressed his readiness to meet with Al-Burhan through the mediation of Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), but subsequently backed out of the meeting, citing technical issues that prevented his travel to Djibouti.

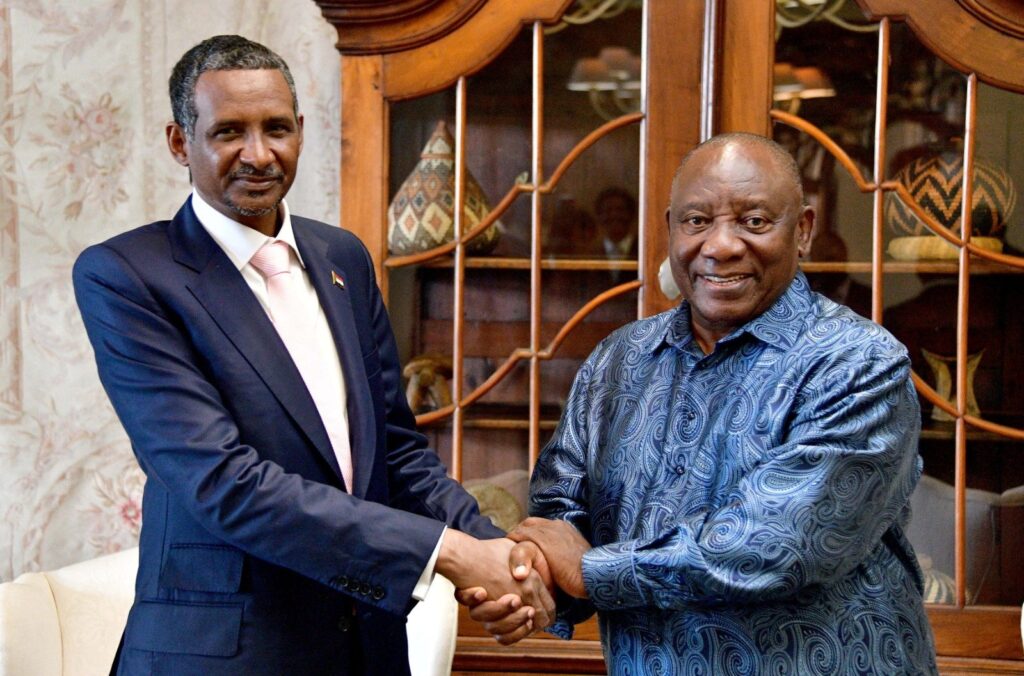

Nevertheless, these claimed circumstances did not stop his arrival in Addis Ababa at the same time, where he capitalised on the lust of the Tagadum front leaders to honour him and sign an agreement with him on 2 January 2024.

Even in this instance, Hemeti continued his pattern of disregarding agreements and failing to follow through on them. Following the signing of an agreement with Tagadum, his militia persisted in destroying, pillaging, and terrorising the villages of the Gezira that it had occupied a few days prior to the signing.

One month later, he cut off all communications and internet connectivity throughout Sudan, consequently disconnecting the final means of survival for the Sudanese and the only means by which humanitarian aid is coordinated.

However, this brief overview of Hemeti’s public career, lacking many details due to the limitation of space, failed to persuade the leaders of Freedom and Change to abandon their attempts to vigorously persuade people that Hemeti is a peaceful man seeking peace in Sudan without personal ambitions.

Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, Hemeti, is nothing but a professional liar, a professional criminal, a professional killer, and a professional mercenary.

Understand Africa’s tomorrow… today

We believe that Africa is poorly represented, and badly under-estimated. Beyond the vast opportunity manifest in African markets, we highlight people who make a difference; leaders turning the tide, youth driving change, and an indefatigable business community. That is what we believe will change the continent, and that is what we report on. With hard-hitting investigations, innovative analysis and deep dives into countries and sectors, The Africa Report delivers the insight you need.