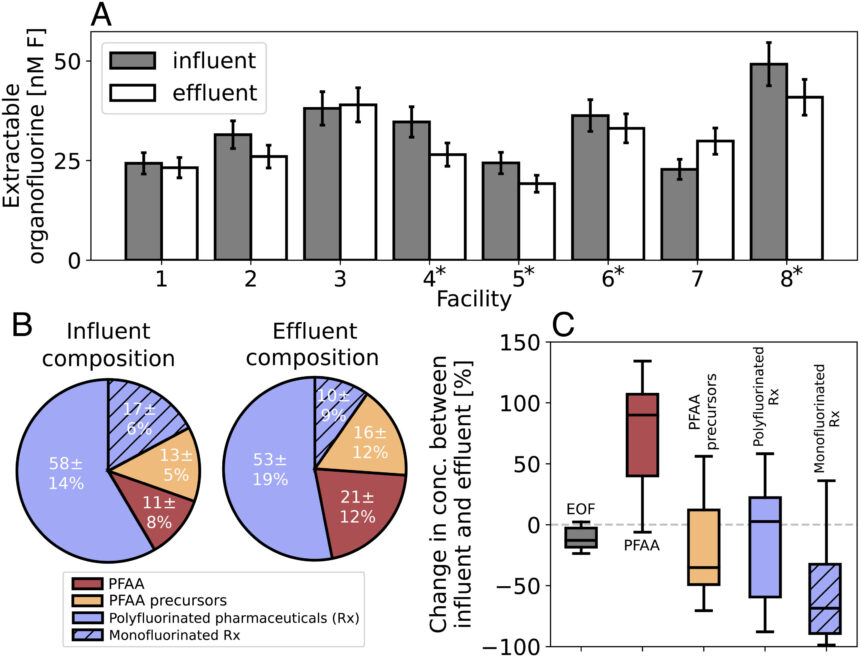

A recent study conducted by a research team from Harvard University has revealed concerning levels of organofluorine in U.S. municipal wastewater. The analysis showed that over 60% of the organofluorine present in the samples consisted of commonly prescribed fluorinated pharmaceuticals, while federally regulated perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) accounted for less than 10% of the total extractable organofluorine.

The study, published in the journal “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,” focused on the detection of PFAS, which are synthetic chemicals with strong carbon-fluorine bonds that are commonly used in consumer products due to their nonstick properties. These chemicals, often referred to as “forever chemicals,” are known for their persistence in the environment and have been detected in various ecosystems worldwide.

Wastewater treatment facilities play a crucial role in managing PFAS contamination, as they serve a large portion of the U.S. population. However, the study found that less than 25% of organofluorine is removed even with advanced treatment processes in place.

The research involved sampling eight large wastewater treatment facilities with similar capacities to assess organofluorine levels. Various methods were used to detect extractable organofluorine, including PFAS, precursors, and fluorinated pharmaceuticals. The study also applied a national wastewater dilution model to simulate how discharges mix with drinking water intakes under different flow conditions.

The findings revealed that pharmaceuticals accounted for a significant portion of the measured organofluorine load, with removal rates not exceeding 24% at any of the facilities. This raised concerns about the potential contamination of downstream drinking water supplies for millions of Americans, as over 20 million individuals were estimated to rely on water sources prone to contamination levels above regulatory thresholds.

While the treated wastewater released from facilities may not directly impact household tap water, it can mix with other water sources and eventually find its way back into the water supply chain. This complex water reuse system highlights the interconnectedness of water sources and the need for effective strategies to mitigate PFAS contamination.

The study underscores the urgent need for improved wastewater treatment processes to reduce organofluorine levels and protect public health. Efforts to address PFAS contamination in wastewater are essential to safeguard drinking water quality and mitigate the potential risks associated with long-term exposure to these persistent chemicals.